Fentanyl exposures rising rapidly in Mississippi

Dr. Brett Marlin is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine and is a fellowship-trained medical toxicologist.

The fentanyl epidemic began around 2013-2014 with a 300% increase in fentanyl encounters noted by the US Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) National Forensic Laboratory System in 2015 and presaged the current epidemic. While several competing and overlapping hypotheses exist for its origin and rapid spread, the decrease in prescription opioids since 2012 has likely contributed to pushing individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) to the illicit market where fentanyl now makes up near 100% of opioids available1,2. In addition to fentanyl, the illicit opioid supply is being increasingly contaminated with xylazine, an alpha-2 agonist used in veterinary medicine3. Xylazine has been linked to an increase in dermatonecrosis observed in individuals who use intravenous drugs, predominantly in the northeastern United States but spreading westward.

While data on intravenous drug use in Mississippi is limited, the prevalence of heroin use may serve as a surrogate. Between 2017-2019, Mississippi had a past-year heroin prevalence of 0.11% - three times lower than the national average of 0.30%4 and a relatively low opioid death rate of 28.4 / 1000 persons. In contrast, Mississippi had an opioid use disorder prevalence of 1.4% between 2017-2019, which was slightly higher than the national average of 1.0%4. Mississippi’s relatively low opioid death rate compared to its prevalence of opioid use disorder is most likely explained by its high rate of opioid prescribing. In 2020, Mississippi ranked 4th nationally in opioids prescribed per capita, behind Tennessee, Louisiana, and Kentucky. The discrepancy in the rates of overdose deaths between Mississippi and the U.S. average despite similar rates of opioid use disorder is most likely reflects the salutary effect of historically high rates of opioid prescriptions leading to a “safer” supply of opioids.

Unfortunately, as counterfeit tablets become increasingly prevalent, this also means Mississippi will become increasingly affected by the Fentanyl epidemic. In 2017, 7% of counterfeit pills contained potentially lethal doses of fentanyl5. This percentage has increased to 60% in 2022. The production of counterfeit pills has also increased dramatically. In 2022, the DEA seized 50.6 million fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills – a 100% increase from the previous year5 – which was a 430% increase from 20196. While individuals with opioid use disorder are the most affected, the adulteration of counterfeit pills with fentanyl also places those who recreationally misuse prescription drugs at risk, especially adolescents and young adults. Over the last year, the Mississippi Poison Center has seen a significant increase in fentanyl-exposures. After recording 44 fentanyl-associated exposures in 2022, the MPC has recorded 56 exposures to date in 2023, with almost half of these exposures reported in the last month. While exposures to fentanyl reported to the MPC have slowly risen since 2018, this drastic increase over the last year portends our relative isolation from the fentanyl epidemic will end.

Solving the problem of addiction and ending the opioid epidemic is obviously complicated and has become increasingly both tendentious and contentious between partisan politicians, but there are evidence-based measures we can initiate as healthcare providers that make real impacts on the morbidity and mortality related to illicit opioid use.

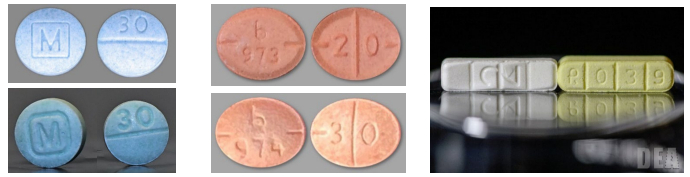

Left: Authentic oxycodone M30 tablets (top blue) vs. counterfeit oxycodone M30 tables containing fentanyl (bottom blue). Center: Authentic Adderall tablets (top orange) vs. counterfeit Adderall tablets containing methamphetamine (bottom orange). Right: Authentic Xanax tablets (white) vs. counterfeit Xanax tablets containing fentanyl (yellow).

The first step is screening and identifying individuals at risk for illicit opioid use. It’s important to use an empathetic or sympathetic, non-judgmental attitude to develop rapport and transparency with patients. Drug testing is not always reliable as basic urine immunoassay drug screens cannot detect fentanyl. Individuals reporting the recreational use of illicit opioids should be educated on the risks of developing addiction and the increased risk of an acute overdose from counterfeit pills flooding the black market. Counterfeit pills are most often marketed as oxycodone 30 mg pills. These pills are often referred to as “M30s” or “Blues” and are round and scored blue tablets bearing M and 30 on opposing faces. Education should extend to the use of other illicit substances as well as fentanyl adulteration is no longer confined to illicit opioids. Counterfeit alprazolam tablets, most often marketed as 2 mg “bars,” have also been seized by the DEA. Fentanyl has also been increasingly found in the U.S. cocaine supply. In 2021, 6 professionals in New York City died within a few days from fentanyl poisoning after using cocaine. Fentanyl poisoning from adulterated or contaminated cocaine has also been reported in Florida and Nebraska, the latter reporting 26 overdoses in an interval of only 3 weeks7. Individuals identified with, or at risk for, opioid use disorder should be referred for treatment. This includes medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) such as buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. Buprenorphine and methadone are both opioid-receptor agonists used to prevent withdrawal, decrease cravings, and restore daily functioning, while naltrexone is an opioid-antagonist that blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids and can suppress opioid cravings. Medications should be tailored for patients individually to minimize the risk of relapse. Naltrexone may be prescribed by any licensed healthcare providers authorized to write prescriptions, while methadone can only be prescribed for use in OUD from a certified Opioid Treatment Program (OTP). On January 12, 2023, the DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) announced the elimination of the X-waiver requirement to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD. Any clinician with a current DEA registration that includes Schedule III authority can prescribe buprenorphine for OUD and is encouraged to do so by SAMHSA. Individuals should also be assessed and referred for concomitant addiction counseling.

Secondly, anyone at risk of overdose, whether from occasional recreational use or those with addiction, should be prescribed a naloxone kit. There are two FDA-approved formulations of naloxone: an injectable and a prepackaged nasal spray. Mississippi House bill 996, the Naloxone Standing Order Act, signed into law in 2017, also allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone under a physician state standing order at a patient’s request.

Mississippi will undoubtedly continue to see a surge in fentanyl poisoning as counterfeit tablets flood the illicit market. Whether you believe in the Iron Law of Prohibition or you believe the need to increase law enforcement interdiction efforts, these recommendations are evidence-based measures all healthcare providers can take to mitigate the impact the fentanyl epidemic will have on our citizens.

DEA Drug Fact Sheet 5-13-21

Sources:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Opioid Dispensing. November 10, 2021. Online at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/rxrate-maps/index.html

- Russell, E. (2023). Rapid Analysis of Drugs: A Pilot Surveillance System To Detect Changes in the Illicit Drug Supply To Guide Timely Harm Reduction Responses—Eight Syringe Services Programs, Maryland, November 2021–August 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72.

- Quijano, Thomas, et al. "Xylazine in the drug supply: Emerging threats and lessons learned in areas with high levels of adulteration." International Journal of Drug Policy120 (2023): 104154.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Behavioral Health Barometer. Mississippi, Volume 6. Published 2020.

- Lassi, N. (2023). Strengthening pill press control to combat fentanyl: Legislative and law enforcement imperatives. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy, 100321.

- Singer, J. A. (2021). Why Does The DEA Wait Until Today To Issue A Public Warning About Counterfeit Prescription Pain Pills?.

- Nir, Sarah Maslin. (2021, Oct. 21). ‘The Cocaine was Laced With Fentanyl. Now Six Are Dead From Overdoses.’